Designing the Planting Plan: Cultural Needs

Blue fescue grass, yarrow, kangaroo paw and rockrose are grouped together in a low-water hydrozone in this Mountain View landscape.

In earlier posts, we’ve written about how we evaluate the types and characteristics of plants when considering selections for our planting plan.

Beyond those physical attributes, there are many other factors that contribute to a beautiful, harmonious planting plan. Chief among these is the cultural needs of a plant: does it prefer sun or shade, clay soil or sand, much water or none?

When new clients describe their ideal garden, they almost always include photos of some plants that perform beautifully in wetter climate zones, but will struggle in California’s summer-dry Mediterranean climate.

To determine just how much supplemental water a plant will need to thrive in a given region, we turn to the WUCOLS database developed by the University of California. WUCOLS classifies more than 3,500 plants into “very low,” “low,” “moderate,” and “high” water needs, and we use this information to group plants into “hydrozones” of similar irrigation requirements. We then can design efficient irrigation systems to deliver the right amount of water to each hydrozone based on the region and time of year.

Like water needs, sun requirements can also be quantified. Plant growers have established conventions of “full sun” (6 or more hours of direct sun each day), “part sun” (4–6 hours of direct sun, primarily in the afternoon), “part shade” (4–6 hours of direct sun, primarily in the morning), and “full shade” (less than 4 hours of direct sun each day). Often a plant will be assigned a range of light, like “part to full sun”; this indicates that it can get by with less than full sun and, in warm climate zones such as ours, may actually need some protection from direct, hot afternoon sun.

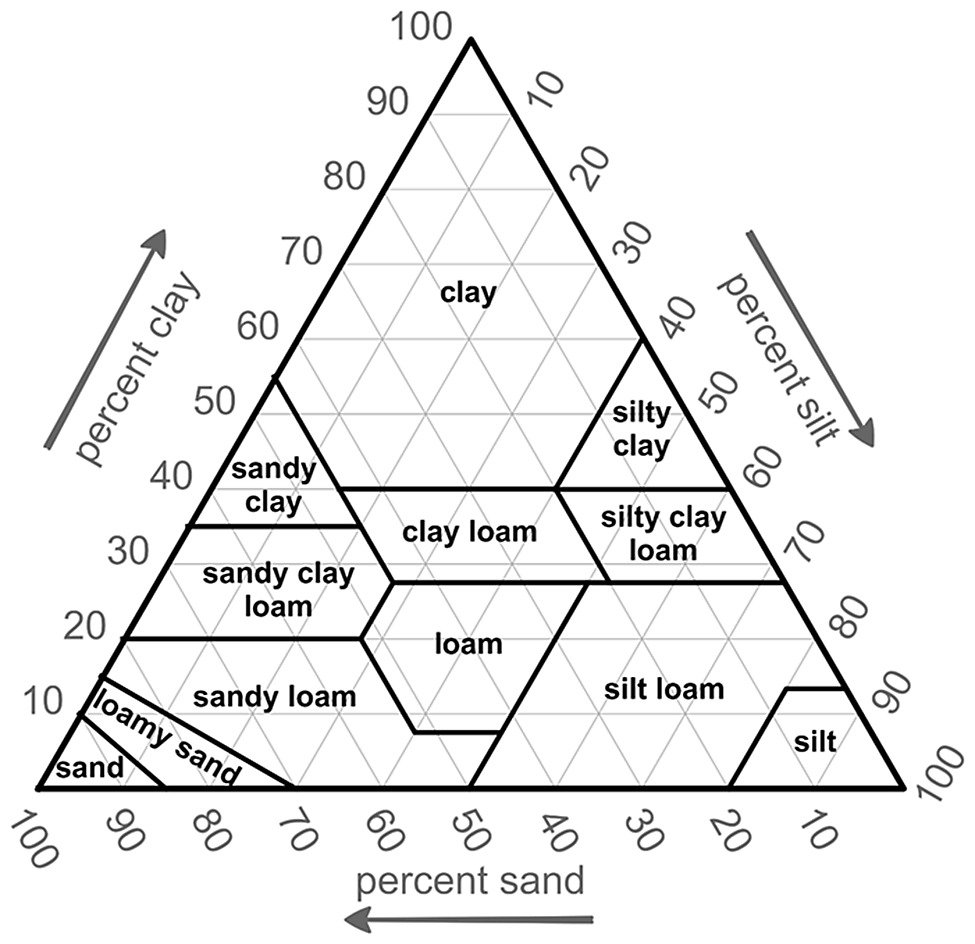

The “soil texture triangle” developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The soil on a site also has a major impact on a plant’s suitability. Soil particles are classified as “sand,” “clay,” or “silt,” and depending on which particles are present in which proportions, the soil may be called any combination of these, e.g. “silty clay” or “loamy sand” (“loam” referring to a soil that has all three particles in relative balance).

California soils are quite variable, and many a gardener working with Northern California clay has struggled to support a succulent or Mediterranean shrub that is native to sandier conditions.

Amending local soil with organic matter to improve its fertility, or with lime or sulfur to raise or lower its pH, can be of limited help, but is impractical on a large scale. For this reason, we insist on testing the soil of a site before we develop our plant list—it’s a lot easier to change the list than change the soil.

Of course, species native or endemic to California have adapted over millennia to our sun exposure, soils, and rainfall patterns, so those are easy winners in our plant-selection lottery.

Beyond that, Sunset Magazine has developed a system of “climate zones” that take into account not only winter low temperatures but also summer highs, wind, rainfall, humidity, elevation, latitude and ocean influence. The terms “tender” and “hardy” indicate whether a plant will die or survive in freezing temperatures; so the same plant may be considered hardy in one climate zone but tender in another.

Knowing which soils, sun, water, and climate zones a species prefers helps us ensure our selections will grow optimally where they are planted. From there, only the experience of designing many gardens over many seasons guides the landscape architect in creating a stunning, unique landscape for their clientele.